John Round

Revisiting the years 1959 – 1968

Brief Biography

Born 1948 and lived in, Thorne, Moorends, Calverton (Foxwood Grove and Broom Road), Accrington, Rochdale, Oldham and Hepworth. Currently retired and living in Cheshire.

Also worked in Grays, Northwich, Ipswich, Chepstow, Leeds, Lurgan, Dublin, Glasgow, Portugal, Italy, Pakistan, India and America.

Worked in; Mining, Aircraft, Textiles, Paper, Plastic and General Engineering.

Father (Bernard) and Grandfather (Andrew) both miners ex. Thorne Colliery. Bernard, retired ex. Calverton Colliery. Maternal Grandfather, John Reed, died 1926 in Thorne Colliery shaft accident. See http://www.dmm.org.uk/pitwork/html/thorne.htm

Favourite books; Non fiction, there’s too much good stuff to mention but The God Delusion by Richard Dawkins has to be up there. Fiction, anything by Ian M Banks.

Favourite websites http://freethenorth.co.uk and http://anotherangryvoice.blogspot.co.uk/

Married in 1975 to Vivette SRN SCM HV: She was one of the midwives to Mrs. Brown the first test tube baby mum.

Daughter: Lisa-Jayne a Copywriter and Digital Artist.

***

All resemblances to real people and places are entirely deliberate

and all mistakes are mine.

***

Published January 2008

Last Edited 2023

I’d be delighted to hear from you especially if you have a mining or engineering background.

With thanks to my daughter Lisa-Jayne for her encouragement and editing skills.

CALVERTON FITTER

School Years

I never wanted to be a fitter and I didn’t even know what a fitter was or did, until it was too late. I wanted to be a draughtsman, just like my maternal Great Grandfather Smith and, extraordinary as it may sound, I didn’t even know what a draughtsman did, until it was too late. Unfortunately, I also had absolutely no idea that a draughtsman was an engineer. However, I was good at Technical Drawing and that was the clincher, although I can’t recall being much good at anything else despite going through school in the ‘A’ classes. I do remember that Great Grandfather gave me his ivory scale rule with his initials, J.T.S., pecked in with a pin; Joseph Tinsley Smith and that sealed the deal.

The school was the Colonel Frank Seely Secondary Modern, at Calverton, about 8 miles north of Nottingham. It is still probably best known for its most famous son Christopher Dean, one half of the Torville and Dean Gold Medal ice skating duo, but that was after my time there which spanned the four years 1959 to 1963. The headmaster during my school years was Mr. Dixon who was described one morning in assembly as a ‘Christian Gentleman’ by the RE teacher who was leaving to join the ministry. I can remember being embarrassed by the whole speech and thinking Mr. Dixon was too. Dixon probably earned his unwanted accolade through his regular and fervent efforts to try to get us to sing the hymns in morning assemblies with a bit more verve but as I couldn’t sing, (though no one noticed) I just mimed a little louder. He was also a member of the amateur dramatic society in Edwinstowe, where he lived, and which he brought to school once to perform a murder who-done-it which was thoroughly enjoyable – I think he played a detective, which was probably fitting to his character.

Some of the other plays I experienced during these years also stick in my memory. A couple of the school trips were to see Shakespeare’s works, including one at the Nottingham Playhouse when it was newly built. I remember being asked to marvel at the new building technique used whereby the wood grain from the shuttering used to pour in the concrete was left on view. Happily the play was good – The Taming of the Shrew I believe.

One sad little incident that has somehow stuck in my mind was the day a boy came to school with a pudding basin haircut his father had given him. Yes, a pudding basin was upturned on his head and his dad had cut and shaved off all visible hair. He looked like a monk and was obviously distressed. Mr. Dixon gave him a notebook to write in the names of all who laughed at him so they could be caned.

It was probably during my final year, that a school trip was organized to a pottery in Staffordshire. The idea I imagine was to show us alternative industries to mining and we were told not to be shy and to ask questions concerning the length of apprenticeship and expected income. As it turned out the apprenticeships were 7 years, which seemed a dreadful long time for what seemed like a rather small wage. Many years later I talked to a man from that area and discovered that in the 1960’s it was common to work a 7-day week for the princely sum of £15. They were proud ‘big money men?- and also known as ‘clay heads’ he confessed. The trip was to end in disgrace however, for during our factory tour there was a general pilfering as students filled their pockets with ashtrays and whatever else they could. A few days later in morning assembly Mr. Dixon told of a letter he had just received from the factories MD and the shame he felt at being refused future visits. I don’t think the hymns were sung with much verve that morning.

Another teacher I recall with clarity was Mr. Cook who taught maths. It seemed his great joy in life was to call us zombies at every opportunity and to praise the merits of apartheid on the basis that he had visited Cape Town on the way home after fighting a war against oppression in the Far East. He told with relish of stepping off the pavement to allow a black guy to pass and being reprimanded by his colleague as it might give the black ‘ideas beyond his station’. I believe it was left to the French teacher to explain how all the countries of the world have had revolutions and they were all justified except for the Irish revolution, which was inspired by songs and poetry. We absorbed it all in open-mouthed wonderment but I do hope there’s no one out there who still believes such nonsense.

I don’t think any of us dared dream that we might one day too visit such places but I have since discovered, on Friends Reunited that one pupil, after a while in the hotel business, bought a boat with his wife and sails the Caribbean. Now there’s the smart fellow. And of course it’s commonplace to visit exotic locations nowadays (and discover they are not exotic in my experience) and www.calvertonvillage.com shows ex-pupils living at least as far afield as New Zealand and America.

Malcolm Nabarro was a friend of mine in the same year and if you Google his name you will find he was a composer, a conductor and the founder of the East of England Orchestra, a marvelous achievement, and I’m a musical philistine. Whilst Malcolm learned music, I sat drawing plummer blocks, any scale, any projection, and I believed I would spend my life doing it for a good wage. One day I sat on grandfathers nice ivory rule once too often, it snapped in two and I threw it away. I was also reasonable at art, I think the art teacher had more faith in me than I did, but I was the reason the school bought its first box of oil paints. I managed to half finish a painting of a potted flower and I also half finished painting the gingerbread house for the school play but I did get credited in the program. But what does one do at art school? And, I was reliably informed, that there was no money in it, whatever ‘it’ was. So there you are, one up and coming draughtsman the plummer block to draw.

Irish Holiday

The best holiday I ever had as a youth took place in the summer of 1960 after completing my first year at the Frank Seely in form 1B and before starting in 2A. I was a member of the 1st Calverton scout troop and we went for a fortnights camping in Glengariff on the west coast of Ireland. The journeys there and back were epics and worthy of a mention. The Scoutmaster was Mr. Palmer a plumber from Woodthorpe assisted by Ian Richardson, nicknamed ‘Gruey’, from Woodborough and there was about 20 of us scouts. Gruey was employed by Rolls Royce and did a degree in Engineering. He once showed me the aircraft engine design he was drawing for his thesis. During the 1970’s the press was full of the problems Rolls Royce was having selling the RB211 engine to American airlines and I have been led to believe that Gruey was one of the team in the negotiations.

We all gathered at the scout hut, next to the Co-op on Main Street and opposite the chippy, with our belongings packed in rucksacks, or in my case a kitbag as rucksacks were more expensive. The whole of the camping equipment, tents, cooking gear, etc, were packed in cardboard boxes tied up with string and we all had to carry at least one of them. I don’t recall how we got to the railway station in Nottingham but from there a train took us to Crewe or Birmingham, then a connection to Swansea where we had a 3 – 4 HOUR wait for the connection to Fishguard. There we boarded a ferry to Dublin, and then a train to Cork, followed by a bus trip to Glengariff and finally a walk of one and a half miles to the campsite. At the end of the two weeks the whole procedure was reversed. By today’s standards of motorways and airplanes and my own later experience of badly behaved boy scouts that is one epic trip for a group of 20 plus 11 and 12 year olds, 1 scoutmaster and his assistant.

On the steps at Nottingham Midland 1960. Photo courtesy of Malcolm Nabarro.

I’ve named who I can but still need some ‘Who’s Who’ input. The old gentleman on the left rear is Arthur Gallimore who was a founder of the Calverton Troop and actually took the first party of scouts to Spain in the 1920’s.

The holiday itself was magic with hot weather mostly; there were lots of games to play and mountains to walk up. Glengariff was an eye-opener and the Post Office was the place we could spend a little time as it was also the greengrocers and we could buy a ginger beer and put a coin in the jukebox. How bizarre. There were palm trees, the first we had ever seen, the weather was so hot and the tent walls were often covered in flying ants.

My end of year exams in 1B had put me in 3rd place in the class, hence my promotion to the A stream, and I had quickly realised that positions 1 and 2 were held by girls – a situation I made the mistake of pointing out so that that summer the refrain, ‘John should know, John came top in the boys’ echoed around the Irish hills in response to most things I said.

This holiday was also responsible for starting me fishing as Mr. Palmer, as a good scoutmaster, had us all poaching in the local river with homemade (camp-made) rods. A few small brown trout were caught but I spent more time scratching the midge bites, as we were eaten alive crouching among the bracken at the river edge.

Throughout these activities we kept an ever-vigilant eye out for the IRA men we were told still frequented the area and who were the reason we couldn’t fly the Union Flag at the campsite. As kids we were actually looking for men skulking about in the hills wearing masks but on the last night the landowner, a Mr. O’Shea, came to our campfire and if the truth were known it was probably him who was responsible.

College September 1963 July 1964

I left school in 1963 with a clutch of 8 passes, 2 credits and a distinction (in technical drawing of course) in the South Notts Leaving Certificate to attend the Arnold and Carlton College of Further Education, a north Nottingham college and where I believed I was on a draughtsman course. (Bring on the plummer blocks). Naturally nothing could have been further from the truth, I was on a full time engineering course – the result after two years would have been a clutch of ‘O’ levels in such esoteric subjects as math’s, science, metalwork and English and one or two others I can’t remember. The Frank Seely never did metalwork, just woodwork and I was never much good, or interested, in that.

Then there was the really scary part. The college lecturers all had a habit of telling us about the ‘cherries’ waiting for us. After ‘O’ levels would be another 2 years doing ‘A’ level’s, more cherries, then there was ONC or HNC or HND, more cherries, then an Engineering Degree. Incredibly it didn’t seem to stop there but my brain was in screaming overload by then and all I could believe was that I would be about 25 before I earned a penny and I was skint already and my Dad had six mouths to feed. It just seemed so totally improbable and impossible. What left my brain quite numb was that there were guys in my class who expected to do just that. I could have nightmares about damn cherries.

The first day at college started with an IQ test that divided us up into appropriate classes and I found myself in E1F. That was scary, as I believed I was in the bottom class (shouldn’t the top class have the letter ‘A’ in it somewhere?) and I spent a lot of time wondering how to stop my dad finding out. It was a number of weeks before I came to realize I was in the top class and much was expected, hence the cherries. How can IQ tests get it so wrong?

That first year was incredibly taxing but I discovered that, just like school, it didn’t really matter if I didn’t do my homework, and the fact I hadn’t read the pre-course reading list in its entirety went completely unnoticed. I can remember Day of the Triffids, Cry the Beloved Country, some autobiography about a civil servant in the South Seas, Metals in the Service of Man and Basic Electricity. It was the last two books I skipped with some trepidation but I needn’t have worried, no one wanted to know. Some of the guy’s hadn’t even bought the books. One of our lessons was ‘Workshop Practice’ where I found myself using hand-tools, lathes, millers and shapers and handling steel, non of which I had done before and had no particular wish to do so then or in the future. It was a rude shock compounded by the fact I was in a class of guys who quite clearly had, which only served to make me panic again and worry about being bottom of the class.

The usual schooldays type of low-level, semi-hidden anarchy existed in the classrooms but with a bit more angst. I’d be sitting at the desk writing and would suddenly become aware that someone had brought in a peashooter to demonstrate his mastery of pneumatics, aerodynamics and being a total prat. I’d be aware because there would be a needle stuck out of the back of my hand with a little paper cone attached. We were also experts at taking a sweet out of a packet, unwrapping it, putting it in our mouths and quietly sucking away without the lecturer (lecturer, not teacher, we were at college now) knowing. “You are at college now not school. You are here because you want to be”, they would suddenly say quiet regularly, for no …err apparent reason.

College started me smoking. Some of the lecturers had a habit of bumming cigarettes from students and there was always a rush to supply and I was suitably impressed and thought it was high time I started smoking as well and so one morning I bought a packet of 10 Piccadilly when I got off the bus. Never did get to supply one but I was soon in the habit of rationing them on a daily basis. One first thing in the college canteen as I flicked through my work wondering which homework I hadn’t done or how to do this that or the other and thinking maybe workshop practice won’t be so bad today etc. etc. One at morning break, one or two at dinner, one in afternoon break, one on the bus going home and that was that until morning again, Dad didn’t discover I smoked for over a year and was a little shocked when he found out. I would always decline the cigarettes he offered me in the house as that seemed to be a tacit acceptance that I was a smoker and in the event it was a short lived habit. (Is that an oxymoron?).

One of the shocks I got that first year was that school friends started materializing on day release. They were being paid to come to college! It was almost beyond my comprehension. A wage of £5 a week was paid for being an apprentice with the National Coal Board for example. It was about a quarter of a full wage for a man with a family to keep. More than a quarter in many cases and I began to believe that I had opted for a bummer. Other guys coming into the college were from the Police, Gas Board, Electricity Board, Water Board and Raleigh Cycles, which just about summed up the main employers in Nottingham, other than the military. What did bring a smile to my face was the sight of a class of police cadets pounding away at typewriters to music. It’s all computers now of course, ‘death by data’ to quote a police expression.

College took us on two excursions that year to see industry in action. The giant iron and steel plant at Corby, Northants, and the Royal Ordnance Factory both somewhere south of Nottingham and representing, though I didn’t realise it at the time, both the beginning and the end of human endeavor if I may display my philosophical bent. The Corby plant was impressive. Impressive in the way that Dante’s Inferno was impressive and I hadn’t even heard of Dante’s Inferno at that time. It was enormous, dark and grim with huge lengths of iron and steel glowing red and running along roller conveyors. There was a Bessemer converter (it converts iron into steel) scattering a drizzle of sparks we had to walk through and huge clouds of orange and yellow smoke roiled into the sky. I couldn’t even fantasize about having any kind of job there. The Royal Ordnance Factory was a bit more like it. All I can remember now is wall-to-wall gun barrels, naval, army and howitzer barrels of all sizes. I saw fitters sat round in a group chattering away while removing sharp edges and smoothing off Howitzer breach blocks we were informed were imported from Italy. I can do that I thought. Suddenly being a fitter didn’t seem so bad. Daydreaming about a life drawing plummer blocks was replaced by a life smoothing Italian howitzer breach blocks.

One of the strangest things that happened that year (since the whole year was strange) was an examination we all took for entrance to employment with Nottingham Council. We were warned not to accept employment offers afterwards and sure enough one day a job offer came through the post telling me (not asking) to report at a particular place and giving me a salary grade. What the job was and what the salary was I hadn’t got a clue and neither had the other guys and the lecturers went to great pains to tell us not to bother. The thought occurs to me that if I’d taken up the offer a whole new lifestyle would have ensured (I could now be a failed chief exec or a highly successful dustbin man!). So why give us the exam to start with? It was all very odd and I never did discover the reason.

Interviews

As the year progressed I felt the pressure coming on from two directions. One was that I was not doing very well academically and the second was economic. In theory I had enough money for bus fares and lunch and my clothes were bought and there was something extra but in practice I was always skint. One particular bad habit that developed was a trip to the pub at dinnertime. We were a group of sixteen and seventeen year olds and not quite sure of our ground but found a pub where we stood in the entrance hall, toilets to one side, bar and lounge to the other and persuaded one of our number to go to the bar for us all after first pressing our faces to the glass door panel and trying to get the nerve up to go in. We did get served and four pints of bitter and lime (bitter and lime for godsakes) were consumed in the foyer with the barman and customers staring through the door at us as we stared back at them and sipped our pints. Then there were the cigarettes and the canteen sandwiches and the result was that I often hitchhiked home and that could mean walking up to four miles of the six mile distance.

Towards the end of the year I affirmed my intention of coming back for the second year when prompted by the head of the engineering department but as I was saying it I knew I couldn’t keep up like this and resolved to get an apprenticeship. I went to three interviews. The first was a disaster and I can only recall the practical test given to all us applicants at the Royal Ordnance Factory. We were sat round a great table with a wire gizmo in front of us and given a pair of pliers and a length of wire with the instruction to make a copy. That was probably the first time I had used a pair of pliers or handled a length of wire if it comes to that and my attempt at the gizmo perfectly demonstrated that fact. The second was an interview for the position of apprentice draughtsman at a small Nottingham company that made rolling stock or parts for it. It became clear that I was not of the calibre required, as I had no O levels and as an apprentice with them they would be funding two years day release for ONC, which was a necessary requirement. If these first two interviews were disasters the third was a nightmare.

Against my better judgment and against everything I had ever said and thought I applied for a craft apprenticeship with the National Coal Board. As a seven year old I had been taken to Thorne Colliery by my Dad and Grandfather to collect their wages one Friday and in the queue they were showing me off to all their workmates and I was led to believe I had been given a job as a pony lad and would be starting down the pit on Monday. I half believed it and was scared witless. Over the years the one resounding lesson that came from the family was, ‘never go down the pit’, ‘get an education’, ‘don’t be working class’, I could see the disappointment in their faces when I told them what I was going to do but I felt backed into a corner and so at least I was going to do an interview.

On the day of the interview and having bussed into Nottingham I needed a bus for Beeston where the NCB headquarters were situated and the interview was taking place. I found one that said New Beeston and got on. At the terminus I discovered I had come to the wrong place but fortunately the headquarters were visible in the distance (in Beeston), over the barbed wire, across the ploughed fields, down the hill and through the hedges. I made it with minutes to spare, a healthy sweat on my face and mud on the trousers of my best suit. Actually it was my only suit as all suits were called best suits in those days and I later discovered many of my friends lived in jeans and a single pair of trousers. To add to the misery I was also in abject fear as I felt I was at the end of the line and if I failed here there would be nowhere else to go.

Once inside I was ushered to a chair facing a row of men in dark suits sat behind desks and shuffling papers and I was so scared I couldn’t even focus on faces and had no idea who any of them were. Then a voice said, “I’ll kick off shall I as John is in my department at college?” Bloody hell what was he doing there? It wasn’t long since I’d told him I was coming back next year. Then things got worse. “What’s two thirds of a half John?” I tried to picture the equation and cross multiply but kept tripping up on myself and starting again and the silence got longer and I could feel myself getting warmer and more uncomfortable. Finally I came up with an answer. I forget what I said but it wasn’t ‘one third’ and probably wasn’t even ‘two sixths’ The answer was repeated at me several times and I just kept on saying yes.

Another voice then said, “I’ll have a go, how do you sharpen a lawnmower John?”

I had no idea but had a mental image of removing the fixed blade and rubbing a carborundum stone up and down it so I said, “With a stone”.

“With a stone?”

Yes.

“With a stone?”

Yes.

“With a stone?”

Yes.

Another voice. “Shall I have a go? How does a toilet work John?”

Christ. Now they were talking about toilets. “With a cistern”. I can feel myself sliding down the pan.

“With a cistern?”

Yes.

“With a cistern?”

Yes

“With a cistern?”

Yes.

Another voice. “Let me try. Are you any good with electrics John, you know, at home or anything?”

“Err, I change fuses at home.”

“You change fuses at home?”

Yes.

“You change fuses at home?”

Yes.

“You change fuses at home?”

Yes.

Another voice. “What makes you think we should employ you John?”

Bloody hell, how in the world would I know that? The next few seconds (and it seemed like hours) was the pregnant silence to end all pregnant silences and I got very hot and flushed and hadn’t got a clue how to answer. Then it was like God helped me out.

Another voice. “Well, would you be punctual?”

Quick as a flash I was on top of the game, “Yes, I’d be punctual.”

“You’d be punctual?”

Yes

“You’d be punctual?”

Yes

“You’d be punctual?”

Yes.

“That’s all thank you John”.

I went home and lived in misery for a while, rehashing over and over again just what had been said, what I had said and feeling the atmosphere engulf me again and again and again. That is until the letter arrived a week later telling me I had got the job.

Apprenticeship 1964 – 1968

It was the start of something different but the old year was not finished. End of year exams (poor), a medical for the NCB and back to college for the IQ tests with the entire years NCB intake where I did well again and was separated out with the minority to go cherry picking while the others did City and Guilds. There was an interview and trip underground with Mr. Metcalfe, Calverton Collieries Training Officer, and every time I said ‘Draughtsman’ he said ‘Surveyor’.

With college over and the apprenticeship starting in August I got my first job as ‘Tea Lad’ on a village building site. We were constructing the bungalows on the estate behind The Gleaners in Calverton and on 6d (2.5p in new money) an hour (the foreman said ‘Apprentices Rate’ the builders said ‘Rip Off’ I made tea, fetched and carried, learned to drive the dumper and played dominoes with the men at 1/2d game. We always were up sharp at the end of the breaks and one day I asked about the strange holes in the walls of the little Nissan hut we used. The foreman has a 22 in his cabin and if we’re late he lets wang at the hut, was the reply. They were probably nail holes but I’d no idea of the truth of it and no one smiled. The foreman also sold cigarettes from his cabin, Park Drives in packs of 10 or 5 and he would split packs to sell them singly.

One of the labourers I seemed to work with regularly explained the very low wage he was on but which would be enhanced considerably by certain fixed price jobs like shoveling a lorry load of hardcore into the dumper which would bring his wage up to a respectable £24 a week. It seemed very tempting that summer of 1964 but August 10th soon came round.

The NCB had a training centre at Hucknall in Derbyshire, just over the county border, and an easy 8 mile bus ride from Calverton. It was an old mine, long ceased production, but underground was still used to train miners and apprentices in basic underground safety and competences while the surface facilities were converted to train apprentices in various basic skills. The steam engine that drove the cages up and down the shaft was built about 1898ish and was made for a ship but the Shipping Company went bust so it was used for a mine instead. I almost want to write that again. ‘Hey, got a steam engine, do you have a ship, mill or mine that needs one?’ What a magnificent and versatile piece of machinery a steam engine is and I’m so glad I never got to work with them because of the stories we were told of uncomfortable working conditions and steam burns.

That first six weeks at the Hucknall Training Centre (HTC) was chaotic. We painted everything, the floors, walls, the rocks in the rockery, the bricks blocking windows open, our overalls and ourselves. College didn’t start until September and therefore apprenticeship proper, the NCB were just giving us a wage to stop the drift out into the Army, the NCB being the biggest supplier to our armed forces. We met some of our instructors, the most noticeable being a big Scotsman whom we where allowed to call ‘Jock’ in a fit of creativity not unusual in young apprentices. Jock would come into a workshop as we were standing around admiring our newly painted floor and spit all over it. ‘Celtic colours’ he explained but which actually explained nothing and left us open mouthed and staring at each other in mystification.

First year proper started with the September college term and was a combination of HTC and College in the ratio of a week and a day at College and four days at HTC. The City and Guilds lads had a different timetable between the HTC and College and that’s where I cocked it all up again. Come that first Monday of apprenticeship proper I didn’t know where to report. I didn’t want to ask at the pit for fear of looking stupid and I wasn’t sure whom to ask among the other apprentices for reliability so I devised a plan. I caught the 7am bus to Hucknall knowing that if I had chosen wrong I would probably have the time to get to college. Two miles out of the village other apprentices suddenly started asking what I was doing there, I should be at college. I dived out the bus at the next stop, hitchhiked back home, I did get a lift, a quick change at home and I just made it for the college bus. How the hell did those City and Guilds guys know? What did I say about IQ tests?

College had surprises. I suddenly found everything easy, I’d done a lot of it before, true, but somehow the plug was out and I understood far more, far better and revelled in a new found confidence. Term work was good, homework got done and end of term exams were all credits and distinctions. I was also getting a wage and felt more positive and comfortable with myself than ever before.

The HTC regime was a combination of work on coalface supports, coal cutting machinery, compressors and diesels including the HTC’s own locomotive. There was a blacksmith’s workshop and an electrical department where we made up simple circuits. I had my first industrial accident here. Sliding a heavy steel underground roof suport along the newly painted Celtic floor it tipped while turning a corner and crushed the tip of a finger. I’ve still got the scar where the four stitches were. Fortunately all my future accidents have been small ones similar to this and only on one other occasion have I needed stitches. Years later I discovered an old habit some craftsmen had of scribing or welding their names into machinery especially if it was exported. I’ve always joked that every piece of machinery I’ve built has my blood on it somewhere.

Jock was big and brash and full of ideas and projects. We stripped a large compressor down under his tutorledge and he was prideful of the fact it was driven by a diesel engine, i.e. the whole kit and caboodle had no electrics at all. He taught us to drive the loco and had us changing the configuration of the railway lines, which ran through the grounds. One Friday, in order to finish the job we had to shorten two lengths of rail and only had a junior hacksaw to do the cutting. They were almost British Rail size and it was a lot of work, which we did in relays. We missed the Wells Fargo (wages van) and had to bus to Beeston Colliery at our own expense to retrieve them.

Another of Jocks ambitions was to start an Engineering Club at HTC, which would mean after hours strip down of the diesel engine (unpaid) and of course we all enthusiastically volunteered. Jock vented his fury on the unknown apprentice who had asked higher management if we would be insured while in the Club and as the answer was no the whole plan was kyboshed. I couldn’t be the only one to be relieved, I just wanted to go home; I didn’t want to be there at all in spite of the fact I did quite well and managed most tasks with a minimum of problems. (No, it wasn’t me).

It turned out that Jock was in the ‘Specials’ and was very proud of the fact. If any apprentice ever expressed to him any idea of discontentment (I was one) he would put on a studious look, pursing his lips while looking skywards and squinting his eyes then appear to have a eureka moment and say, “I don’t know why you don’t join the Po…leese Force as an Engineering Officer”. He did it with everyone. A few years later I made such an enquiry and the policeman on the phone burst out laughing. When I told him it was a Special who had advised me he commented there was always one who was very special. Amen to that.

I forget the blacksmiths name but I remember him. He explained the anvil and how it worked and the swages and other paraphernalia of a working Smith and he got steel hot and we learned how to be a Blacksmiths Striker and then we had a go at being the Smith ourselves and eventually we made steel links with some of us, (but not me), managing to make two interlocked links like in a chain.

We also learned sexual innuendo with a vengeance. He would have us in a semicircle round the anvil while he showed us a technique then suddenly circle his thumb and forefinger and say, “Its only a little hole with a bit of hair round it, what’s the problem?” As a gang of adolescents we would be in a continuous state of giggles or outright laughter at his antics. Another one was to clench his fist and extend his middle finger and slowly pass it round the semicircle. “You all know what this is for don’t you?”. There was no letup. How embarrasing.

We were in the Blacksmiths when the case of the top button came to a head. There’s always one with the biggest fists, the loudest mouth and the most friends and this fiend took it upon himself to rip off the top rubber button of our overalls. His closest ‘friends’ just stood and let him, and some even did it themselves to prevent any conflict, while most of us were just caught unawares at different times. I was the last and while in the Smithy noticed furtive eye movements, sly grins and a general move in my direction and the Smith was out, probably sneaking a fag, so I armed myself with a small piece of steel which I could legitimately have to make a link. When the expected move was made, the quick grab for my top button, I feigned surprise and in lifting my hands up to protect myself I made damn sure the steels sharp edge raked his hand. I’m still pleased to report that blood was shed and when the Smith came in he escorted him to the first aid room for a small bandage.

Later, with the Smith supervising, and us trying to make links, he came out with, “We all know what a c**t is don’t we?” looking intently at me, but happily there were few giggles. Our very own ‘alpha male’ had obviously grassed me up and what he was going to do to me when we left the Centre had me scared, but in fact nothing happened. I was the only apprentice to escape with his top button intact.

There were other instructors naturally but no names or faces come to mind. Like most of the people I’ve ever met they were just there and doing their job.

At the centre, and as part of the sylabus, we were shown a series of films about mining, safety, geological strata and other subjects. All very interesting first time round but on occasions, probably when the tutors had run out of stuff for us to do, we got resits and it all became extremely boring. We all sat there in the darkened room trying to stay awake, getting a crick in our necks and shuffling about on our seats to try and keep our eyes open. What joy!

Calverton Colliery

That first Christmas Holiday, with both College and HTC shut down, came with some apprehension, as it was the first time I had to report to my own colliery, Calverton, to work. It was a shocking and frightening experience. The days were long and cold, they seemed to last forever and there was a host of new people and names to try and get used to. I was put in the surface maintenance workshop, a vast room with a few machine tools, the blacksmith’s forges, three of them, at the far end and the foreman’s office up some wooden stairs where he could see all that was going on. We could have a ten-minute tea break in the morning and afternoon, as well as half an hour’s dinner. Most of the fitters made their tea in a white enamel billycan and the lid was the cup. Each ‘brew’ would be a square of newspaper folded around a spoon of tea and a quantity of sugar brought from home, put into the can and then filled with boiling water. The milk was usually bought from the canteen, or brought in a small bottle from home. We couldn’t even sit down for the ten-minute breaks but had to stand by our benches and, bang on time, the foreman would be standing at the top of the steps.

There were a few of us new starters and naturally we were fair game for a lot of good natured banter and were split up to work with different fitters. I seem to have drawn the short straw and had to assist a bad tempered individual with some humping and shifting. He was middle aged, probably in his forties, with an unhealthy looking red face and a sharp tongue. “Get hold of the end of that beam and lift with me”. Before I’d got hold of it properly he’d lifted his end and caused me to get a nasty gash in my hand, oozing blood. He saw this and was immediately shouting to others, “Watch this one he’s a killer, watch this one he’s a killer”. I was so embarrassed and I spent the rest of that shift trying to hide the throbbing cut and mopping blood. He died of a heart attack just a few years later.

Those weeks didn’t improve and neither did the ‘pit weeks’ at the Easter college break. It was a time of long hard days, working mostly in the coal preparation plant which was situated just to the north of the pit proper over the public road to Oxton and connected by the overhead conveyor belt which was also the main walkway. The prep plant was not only dirty and noisy but the whole building shook as well. This was the place where the coal was separated from any stone and was washed and sorted into different sizes and loaded into railway wagons for transit elsewhere. As an apprentice it was my lot to do the fetching and carrying and cleaning. Typically I would be sent to the stores with a list of pipe fittings to get, not written down, as no one seemed to carry paper, but in my head. Things I didn’t understand, and had never heard of. I often got it wrong and had to make another long cold trudge back to the stores. One of the jobs needed a lot of water and someone had the great idea to use the large emergency fire hoses coupled together to give the length we needed. The first attempt failed as there were too many holes in them, they were made of canvass and were probably mildewed and water was spraying everywhere. It caused a lot of concern because they were supposed to be in working condition and ready for an emergency. We did get a combination of hoses together eventually that did do the job.

As with most of the large places I’ve worked at there was someone running their own ‘shop’ and in this case it was exclusively durex condoms. When this fitter was in the prep plant he would be heard shouting “Johnybags for sale” as loud as he could over the noise. It was strange looking out of a window at Oxton woods and recalling that not long ago I had been playing and exploring over there and wondering what this huge building was all about. Well now I knew – and I preferred the woods.

One strange story I overheard was of one of the prep plant workers being heavily fined for speeding in his car and the magistrate was a colleague at the pit. I couldn’t credit this at all, a pit man as a magistrate giving out fines to his mates. Magistrates were like judges or something and that was their job, wasn’t it? I heard the story again from another source and so figured it must be true after all. This is a basic bit of general knowledge and the old Frank Seely seemed to have let me down badly, unless of course I’d had a day off school with a headache when they did magistrates. At least I knew about the Irish revolution and apartheid!

I’ve no intention of making a diary of those apprenticeship days and writing down main events I find it impossible to put them in chronological order. Basically the second year was spent on the pit top and either at the end of the year or in the third year I did underground training spending my time afterwards with underground fitters and then at the end off the third year I did coalface training and the rest of my time there was coalface maintenance.

Outward Bound

During June of 1965 and still in my first apprenticeship year I got the opportunity to go to the Outward Bound School at Ulleswater in the Lake District sponsored by the N.C.B. It was a month of mountain walking, rock climbing, canoeing, camping and generally having a good time in the great outdoors. The only downside was having to jump into Ulleswater at 6am every morning. Incredibly there’s a picture on sale in IKEA of a photo of the very jetty we had to jump off. My daughter had it hung on her bedroom wall for a couple of years and got tired of my references to it.

At the school we were split up into manageable groups (patrols) and my lot were dormed in the old stables of the great old mansion which may sound like the short straw but it was an extremely comfortable place. Mind you we never did get to see the others accommodation. We had fire evacuation practice one day which involved the school abseiling from the upstairs windows. The fees for the school were about £60 for the month, an enormous sum, and it was clear that most were from the public sector. The Fire Brigade, Police, Coal Board, Electricity Board and Water Board were all represented and there was even someone from Raleigh Cycles. One lad was an engineering apprentice at Fords at Dagenham and would suddenly say, ‘Ford Engineering’ with obvious pride and then another time ‘Ford Engineering…shit’ with all the distain of a knowledgeable insider. He was obviously too young to be doing anything else but mirroring verbal experiences. The biggest laugh was reserved for the lad who, when asked who sponsored him, replied in a most refined voice, ‘My Mother’.

When mountain walking we had to leave messages in tins which were hidden in the rock cairns which are found on the top of all hills. It enabled the instructors to keep tabs on where we were, especially useful in bad weather. We were advised to put useful information in the message, are we making good time?, what’s moral like?, is everyone ok?, are you going like dingbats? Etc. It was amusing to read previous messages left in the tins that had not been collected by staff. E.g. ‘We’re cold, wet through, we’ve been lost, we’re hungry, we’ve got blisters, and we just want to get home. Going like dingbats, moral high’. Every time since when I’ve been in the mountains I’ve looked for and found these types of message, and they are still amusing.

The downside of the school was that it had an adverse affect on my academic career as canoeing first and then rock-climbing took over my weekends and most of my mental activity. It’s not what the Outward Bound Schools were supposed to be for. I did give up smoking though.

Sometime into my second year as apprentice I made contact with the Nottingham City Kayak Club and spent many happy weekends, body and soul, paddling on the Trent and going for weekends away to such exotic places as a National Canoe Sprint at Reading and Surfing at Wells Next to the Sea. The Club started at a basement next to the Nottingham Canal, I saw one girl demonstrate capsize technique and there was a leach stuck to the bottom of her boat. No thanks. I helped to build the first Club House on the Trent Embankment out of enormous packing case sides. I understand that it is now a superb brick facility and one of Britain’s best clubs producing Olympic paddlers.

What I didn’t care for was the organization that went into canoeing. I couldn’t go alone, I had no canoe, and they were expensive. Safety dictated a minimum number and to include experienced paddlers. Transport also dictated a car and economics, for me, suggested a motorbike, most of my contemporaries seemed to have them and I’ve never seen a motorbike carrying a canoe. I’m being unfair but youthful emotion got the better of me and I faded out to spend my time mostly hitchhiking into Derbyshire and further afield to go walking and rock climbing.

Second Year

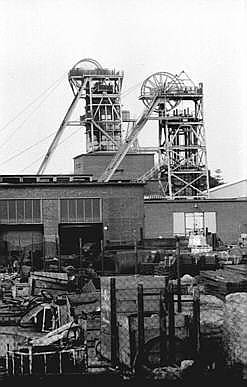

Calverton Colliery headgear. Photo courtesy of www.mining-europe.de

The second year was more interesting and I was less fearful and awed by my working environment and apart from one day a week at college (no more HTC) was mostly spent on the collieries surface and included shift work. One Sunday morning, and I mean 3am-4am; it came my lot, with a fitter, to lubricate the rope on the larger winding engine which brought the coal out of the mine. First job was to fill a bucket with the necessary warm oil and carry it up the steps on the outside of the steel gantry that can be seen carrying the large winding wheels on any pit top. Sounds easy but it was January, with sleet in the wind showing up in the yellow sodium lighting, the steps were slippery and I had to hold on and pull myself up with one hand while the heavy bucket was in the other and in spite of the heavy work I was freezing cold. Next task was to take my donkey jacket off, rollup my sleeves, insert my hands in the oil, lift some out and slop it onto the huge steel rope as it came off the wheel. The winding engine was run at a special slow speed so I could keep dipping into the bucket for more oil. Today’s health and safety people would probably have kittens but thankfully I never had to do it again.

All us apprentices had to spend six weeks in every pit top department, though it usually ran over that time. The foreman took me into the loco shop, which was staffed by a fitter and charge hand and there was a Rolls Royce Engine parked in it and when the foreman introduced me he said I had to be able to strip and reassemble the engine before I left that department. It was a joke, naturally, but I didn’t realise it at the time; I was still the tea lad and guffer. On an icy cold winter morning some of the loco’s had to be started by the method of removing the filters from the engine air intake and lighting a fire with paper and wood in the air manifold. After a few minutes the fire would be raked out, the filters put back and the engine would start because of the warm air being pulled in. With others a plug would be removed from the cylinder head and a special syringe of warm oil injected into the head, the plug replaced, and the engine would start. The oil had been first put into a tin and the tin put onto a twin bar electric fire turned on its back. It was a dangerous practice and I was duly warned to be careful as a previous apprentice had dipped his finger in to test for temperature and when he removed it a drip of oil had hit the fire, ignited, and flared up giving him a bad burn.

One day I made the chargehand cry. In making the tea I dropped and broke his mug. It was supposed to be white but it wasn’t, it was a web of cracks and chips that oozed a brown biological, primordial gunge. If it had been struck by lightning we would probably be at war by now with a new species of life form trying to take over the planet. Afterwards the fitter told me that the chargehand was so upset his eyes flooded as apparently he’d had that mug eighteen years. Its an odd thing but years later I was told I’d made another guy cry by using his mug when a temporary contracter took mine. Wot is it wiv people?

The loco shop was where the colliery manager had his car cleaned every Friday and it was my job to do it. It was a brand new green mark one Ford Cortina and the first car I ever cleaned. They laughed when I said I’d finished. Turned out I had to give it a full valet and a good waxing. It took half a shift every Friday and to this day I’ve never cleaned a car so well.

One of the spectacular moments of the apprenticeship was the shaft inspection I did one weekend with the foreman. Periodically someone had to ride down the mineshaft on top of the cage and visually inspect and take frequent measurements of the steel guides that held the cage in position as it rocketed up and down. So one day I stepped gingerly onto the cage top with a safety harness on and clipped to the shackle arrangement that held the large steel cable. The foreman had his gong and hammer, for signaling stop and go, and a vernier calliper to measure the guides and off we descended at the necessary slow speed. We stopped often, a bang on the gong, heard by the banksman who sent his electric signal to the man controlling the winding engine. We used our cap lamps for a look around, took the necessary measurement then two bangs on the gong to get us going. Halfway down the ascending cage passed us and I was transfixed with awe at the spectacle. It was breathtaking to be perched on top of that cage with another one slowly passing upwards and to see the mouth of the shaft giving some illumination from far above and with my cap lamp splaying about. The foreman kept saying, “Don’t look up in case anything falls”. He was wasting his breath. It was just too awesome.

Calverton worked the High Main coal seam and when we arrived there I discovered that it wasn’t the actual pit bottom. There was another seam further down that had been previously worked out by Gedling (or Beeston?) and the shaft needed inspecting down to that level and a water pump turned on for a short while. The trouble was that we couldn’t go down on the cage as the other cage was at pit top and was attached to the other end of the same rope. If we went down the other one would be up in the headstocks and in any case the safety systems wouldn’t allow it. The answer was simple. In the floor of the cage was a small hole covered by a plate, which was removed. The cage was raised about three feet and a small wire rope was fed through and fastened to a shackle in the cage roof. The cage was then raised until all the rope was unwound from its creel and this was the exact depth to the next coalseam. On the end of the rope was attached a large steel bucket. We climbed in the bucket which was swung out into the shaft and when it had settled down the cage was lowered gently back to High Main. Underneath was the long thread of rope with its bucket and the foreman, his gong and myself. The bucket swung round and back through nearly ninety degrees as we descended and seemed to be hopelessly inadequate for the task. Halfway down it was the foreman who looked up and said, “Hope those bastards don’t piss on us I’ve had the golden rain once already this week”.

This foreman was a contrary fellow and I never new where I stood with him. At the top of one of the mineshafts was a network of steam pipes, which were leaking badly and I was assigned to help a fitter repair them. The steam was turned off and the pipework stripped out and inspected. The trouble was that all the universal joints were badly corroded and needed replacing but we didn’t have any new ones. The fitter told me to go to the foreman for some emery cloth so we could rub the seal faces down and do the best we could. The foreman gave me such a bollacking and in a rather more colourful manner said, “You don’t use emery cloth on universal joints; you use valve grinding paste and grind them in properly”. He then gave me the emery cloth.

I had been sent to him for an NCB donkey jacket soon after starting and he’d looked at me, sizing me up, then said, “here you can have mine” handing it over. He would then go and collect a brand new one from the stores for himself. The men would shake their heads at this practice as he did it to everyone who was of similar size and most of them had also been victims. It backfired eventually though to everyone’s amusement when the new batch of donkey jackets turned out to be of a more lightweight inferior quality.

This foreman had one of the blacksmiths make him a central heating system for his greenhouse and then, a few months later found that the smith was making a swing for his children and storing the parts in the underfloor flue for the hearth. He removed the parts and scrapped them. I also found that it was possible to identify where the blacksmiths and strikers lived in the village by virtue of the fact they all had wrought iron scrollwork in the frosted glass panels which ran up the sides of all the front doors in the coal board houses.

These blacksmiths were a strange bunch of guys. There were three of them, each with his own striker and one of them specialized in the hot melt swaging of wire ropes while the other two did more general work. Sometimes miners would come into the workshop to have their chisels sharpened prior to going underground on the afternoon shift and a blacksmith would heat it in his fire with the miner looking on and draw the cheeks of the chisel out on the anvil then sharpen it on the grindstone and then the miner got a surprise. Instead of it being handed back to him the blacksmith would get it red hot and sling it under the heath and tell him to come back tomorrow. This was a necessary part of the ‘normalising’ process prior to hardening and tempering which could only be done when the chisel had cooled naturally. The miner didn’t know this, the blacksmith new the miner didn’t know but always chose to upset them in this manner.

The blacksmith specializing in wire ropes was held out to me as an example of what I should be doing in the summer as he took his family to Corfu every year. I barely new where Corfu was and found it extraordinary that anyone should want to go there. “Look how healthy and fit he is” I was told, “It’s a lot better than putting your boots on, carrying a rucksack and walking up them hills”.

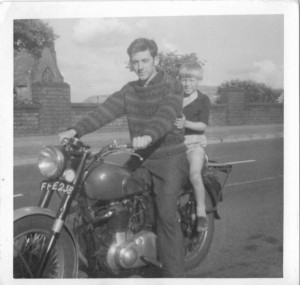

Motorbikes

These apprenticeship years were motorbike years. We lived and breathed them. Mike Hailwood was king of the track and one apprentice even had an LP record that consisted entirely of the sound of bikes passing a particular point on the Isle of Man TT race. Just how cool is that?

Wage = motorbike. It was as simple as that. I didn’t even have to go looking for a bike, it came to me. It was a James Colonel 225cc of 1954 vintage and was brought round to my house by a guy I knew who was in the year higher than me at school and had heard I wanted one. He asked for £10 and I didn’t negotiate I just told him I had no money. He asked for 10/- per week and it was a done deal. He left the bike with me and every Friday for the next twenty weeks he sent his little brother round for the dosh.

This was my first close look at a bike. It was a wreck. It looked tatty and was tatty. The engine was a slow Villiers two stroke single cylinder and nestled in a frame that was big and heavy and battleship grey and about as sexy as Bernard Manning in a mud bath. This model was only made for two years and I believe that’s the length of time it took the MD to find out what they were making, say, ‘James Engineering – shit’ with all the distain of a knowledgeable insider, and shut it down.

The rear tyre was bald, the wheel rims had lost all their chrome and the overcoat of aluminium paint was peeling. Numerous wheel spokes were loose. The seat was ripped and so was the seat cover. The seat was held on with string. The drive chain was so stretched it was trying to ride over the rear sprocket and had numerous split links where it had broken. The clutch was slipping. The spark plug was loose in the cylinder head because the threads were about stripped and soon did. The throttle cable would open but not close (nearly killed me first ride out). The rear suspension was shot; it was all bounce and no damping.

My dad was not impressed. “You’ve only got it so you can practice fitting”. The truth was I got it because I didn’t know any better but I did set about fixing and replacing. My first big purchase was a rear drive chain and when I went for it I discovered I didn’t have enough money. So I bought half. To this day I can’t believe I was so stupid. I got home and actually fitted it to the bike using half of the old chain. In any gear the bike now had two speeds depending which part of the chain was on the sprocket as the old one rode out of the teeth so changing the speed. It was the strangest jerkiest ride ever and of course I had to give up until I could afford the other half.

The guy who sold me the bike told me how to get a ‘ton’ out of it. It was basically a list of the adverts in the magazine ‘Motorcycle Mechanics’ which was our bible. Clipons, rear sets, ally tank, ally wheel rims, skim the head and put on a fairing. It still wouldn’t have done it. One week M.M. featured an article about the safety of bikes and one of the items was that bikes don’t have head on collisions with each other. I did, coming round a corner in the village one day and because the suspension was shot and bouncing I lost control, veered onto the wrong side of the road and hit a motor scooter head on. The scooter was owned by a ‘mod’ and was resplendent with all the usual add-ons like car wheel rims and arials. Happily my bike didn’t suffer but the scooter had a few quids worth of damage and I felt obliged to pay up.

I did get my James fixed up eventually and it did prove reliable with a top speed of sixty miles per hour and I also found a way to make it go round corners better. About two pints of best bitter!

My second bike was a different beast altogether. One of the Blacksmiths told me his son had a BSA A10 650 twin and it was for sale at £10. It had a cylinder head gasket leak so there was oil oozing out but other than that it was OK. Done deal. I think it was a 1954 model and had plunger suspension. None of this modern shock absorber, damper stuff like the errr James Colonel, but still the next step up from the original solid frame bikes.

In the village was a large house situated by the schools and the top estate, on Flatts Lane that had been surrounded by a piggery but the widow found a more lucrative income by converting it into a covered car parking area. In the corners of this large area were lockups and I hired one of them. I believe the rent was something like 2/6d per week and with the overtime I was getting and the shift work premiums it seemed like a good idea. This was where I stripped the bike and did all the cleaning, painting, general renovation and engine strip down.

While the bike frame itself was in sound condition the engine was in a whole different league. Not to put too fine a point on it, it was knackered in every department. When I told the blacksmith what his son had sold me I got two minutes silence. To the rescue comes the nephew of the local vicar (he was the Rev. Hoyle but I can’t remember the nephews name) who just happens to have an A10 engine in bits in the vicarage garage and for a fiver its mine. Between the two lumps of aluminum and iron a decent engine is assembled. Most of the work is done between three of us. John Wood and Martin Hanney were longstanding friends and we sat in my workshop, by candlelight, cleaning paintwork, polishing aluminum and doing all the assembly work while talking about getting a sidecar for it and going off mountaineering in Scotland.

The day finally arrived to start the engine up and it fired on the second kick. It ran for about 3 seconds and seized up solid. When I stripped the engine down again I find that I have omitted the plug, spring and ball that gives it oil pressure. The oil was pumped directly into the crankcase instead of through the main bearing and big ends. So now I decide not to leave it to chance but to spend a little money and get a proper job done professionally. See, I’m twenty years old and still not entered the real world. The crankshaft obviously needs regrinding and new big end shells fitting so I carry the two crankcase halves, crankshaft, con-rods and camshaft into Daybrook on my James. The parts are in my rucksack on my back and just about cripple me. The bike dealer in Daybrook has a really impressive shop. There are frames and tanks and fairings and all manner of goodies hanging all over the place. They were people who obviously know what they are doing and £10 is the quote for a regrind, new big-end shells and the unit assembling properly.

Come the big day and I go to collect and pay my money. “They don’t last very long you know” say’s the guy taking my dosh, and another guy working there says similar. I’m smug, I know better, I know they are about the best engines and I intend to look after it.

I did one return trip to Accrington and I hear a little knocking. It gets worse over the following few days until I limp home and just make it onto my road when it gives an almighty bang and the lump seizes solid. I can’t understand what’s wrong (got a big end loose in my brain) and decide to strip it down pronto. I’ve had these engines up and down so many times now that it was out of the bike and in bits in one and a half hours flat. The big ends are shot and one of the con-rods has broken free and jammed against the crankcase smashing a chunk off the cylinder spigot just for the hell of it. I can’t understand it, the engine has not done a thousand miles and I nursed it all the way. You can’t go mad on a plunger suspension bike; they go round corners like a pig. You have to treat them with respect (not like a pig).

What’s happened is that I’ve had my £10 stolen. It hasn’t had a regrind and new shells; the shop has just botched it up. But I’ve had enough and I can botch up with the best of them and I was not going to spend another groat on the bike. Between the two engines there was a whole one and I duly assembled it over the next couple of hours. The barrel I used was completely worn out; well I’d bought it as a going concern. The two con-rods I used were bent so, not having my tools at the house I used a house brick as a hammer to straighten them on the doorstep and filed the old big-end shells to fit. It all went together and kicked up first time. Boy was it noisy, you could hear the piston rings hitting the step at the top of the barrel where it was worn. What I needed was a buyer who thought it was just a loose silencer.

I drove it up to my workshop and attached a sidecar to it that I’d acquired for 10/- and let it be known that I had a combo for sale at £10. A week later a miner called in to see it and was impressed. He needed something to drive his family around in and this was just the job. Pity about the rattle in the silencer he said, but he could let me have £7.10/- now and give me the rest in a week when he’d been paid again. It was a done deal. A few weeks later I heard that he’d said, “There’s no way he’s getting the rest of it”. I imagine he actually said something a bit more colourful.

Before I leave the subject of bikes I must mention a Scotsman who used to hang around by the name of…err Jock. He had a Triumph 650 single carb Trophy which was a magnificent bike and he even let me have a little drive on one occasion. He came from Glasgow and in the summer when visiting ‘home’ would head west from Gretna Green and take the long coast road back. It sounded brilliant the way he described it. Then suddenly he started turning up at the garages without the bike but as he had his large Alsatian dog with him it was a while before I asked about the bike and discovered that he had lost his mental big-end. He was walking the dog down one of the local lanes and came across a container in the ditch that looked full of oil. ‘This looks good oil’ he told the dog, lugged it home, did an oil change on his Trophy with it and the engine promptly seized up after just a few seconds.

Calverton had a plumber who’s mode of transport was a motor scooter with sidecar on which he kept the long tube containing copper pipe and his tools. I’ve never seen one since but google images shows a wealth of variations.

UNDERGROUND

Later in the 2nd year, when college was finished, I went back to HTC to do underground training for a full week. It was the first time I spent so long down there and we were under constant supervision and learned all manner of basic stuff from health and safety, underground terminology (very important, got to know what people are talking about), to fixing rolling stock to endless ropes which moved constantly between the rails. An exam (theory and practice) at the end (no problem) and I was qualified to work underground, but not coalface. That was to come later.

The remainder of the second year and third year got a bit more exciting as I was sent underground for most of it. Not on the coal face as I hadn’t done the appropriate training but I was working with the pipe fitters mostly although there were times I helped assemble conveyor drives and assisted with other tasks. No welding underground naturally so we stopped leaks with patch clamps and there were always new pipes to be laid somewhere and all the threading was done manually. It was often heavy work.

The main pipe fitters were Les and Frank and Les quickly showed that he was master of the game while Frank effectively, hadn’t got a clue. When they worked on the same shift together on a project it was Les who had command of what was needed and what went where and Frank who was just not with it at all. Back in pit bottom at the end of the shift, Frank would rush to see Billy, the day shift underground engineer, in his office, to give a list of valves and parts needed and at the end Les would call out, “That’s four valves Frank, not three”. And Frank could be heard, “Oh, yes that’s right, its four valves Billy”. Frank just didn’t have a clue and Les would play him for the sucker like that all the time. It was a double joke really as Billy was the lay preacher at the Methodist Church and Frank never missed a service.

One day in August 1966 I got back to pit bottom as the afternoon shift were arriving to find everyone having a good laugh. The Beatles had released their new single and general opinion was that, “There’s no way that’s going to number one”. Then the pit bottom rang to the chorus as everyone joined in, “We all live in a yellow submarine………”

Another thing that started happening to me was to be told off by miners for ignoring them out and about in Calverton, or ‘not letting on’ as they would say. The problem was not that I was being ignorant but that I didn’t recognize them in normal clothes, without a helmet and wearing different spectacles. I had to start taking more notice and nodding to everyone I passed just in case.

I heard the word ‘inflation’ for the first time in the underground office/workshop and I remember it in connection with a derisory wage offer a subject much debated but which went completely over my head. I new I was in the union but didn’t know anything about it and had never been introduced to any union official of any sort. The strangest thing I heard was “The secretary’s in the managers pocket”. It was common parlance but I had no idea what it meant.

Getting out of the pit was a frequent subject of conversation and a couple of fitters I worked with had left but returned to the pit again. One had got a job as a fitter in an American owned company in Nottingham and told of having to stand up and mime having a pee to the boss on the balcony just to go to the toilet. The key to the coal board appeared to be subsidized housing and the coal allowance otherwise I got the idea everyone would have left. I can remember being told many times that NCB apprenticeship wages were good to start with but trailed off and became less competitive later on, it was just a ploy to get the ‘kids’. It didn’t seem to tie in with experience though as the fitters couldn’t find jobs elsewhere and the Nottingham Post Adverts were essential reading.

While I was there a fitter did leave and he emigrated to America with his family. There was a letter from him and he was working as an aircraft fitter somewhere and then went into a lot of detail about how big his car was and its mpg.

Another subject was immigration and I heard a lot of what I now know as racism but was then just another subject to argue over and I’m glad to remember that there were arguments which means, ipso facto, there were anti-racists. Some appalling things were said like one guys description of how Indian girls lost their virginity, which entailed their father, the kitchen table and the use of a razor blade. The story was told with relish, the idiot was probably exited by his fantasy. The xenophobes were also homophobes and actually believed that the Roman Empire fell because of homosexuality. Perhaps they were just annoyed because they didn’t speak Italian? There were always fitters who wanted the government to ban my rock climbing and mountain walking activities as there was always someone getting into difficulties and needing to be rescued. I also learned that syphilis comes from camels and the National Health Service is a bad thing, it was better when the local doctor sent a collector round the estates for a 6d subscription. Oh dear. Its actually true that most of this nonsense came from just a few individuals but they were very vocal.

Probably the most popular subject to discuss was cars. Weekends were the time of car maintenance and weekday discussions evolved round the coming weekends project. There’s a whole vocabulary that’s disappeared from our language. ‘I’m doing my little ends on Sunday’, ‘Got to do a de-coke this weekend’, ‘Changing my valve guides soon as Bill’s finished with the valve spring compressor he’s borrowed from Pete’ So it went on. Some of the fitters made a point of never doing maintenance work, they would buy an old car with a full MOT for the princely sum of £10 and make it last until it was un-MOT-able, scrap it or sell it on and then buy another. Others spent everything they could on a car then garage it for the winter, rust being the big devil.

These were the days of major travel expeditions via pre-motorway roads. While Mablethorpe and Skegness were the main holiday destinations for Nottingham folk some made the annual journey to Blackpool with their families tucked into their little Austin A40’s and Ford Anglia’s, careful maintenance checks followed by apprehensive and fraught 5 hour noisy and bone jarring epic’s to be talked over and dissected more than the holiday itself with workmates two weeks later.

There were two other fitters worth mentioning that worked underground, but not coalface, and they were simple souls. I try not to be disrespectful but I do mean that they were not the sharpest knives in the draw and it looked to me that they were kept out of harms way and given the more simple tasks. In other ways they were heroes. I believe they only earned about £14 per week and were married with families. On one occasion I caught the loco out to a district with one of them and we got the last two seats. It happened that I was facing rearwards and he faced forward and he asked to swap. I declined and said, “Why? Don’t be silly”, but I soon found out why as he became terrified and cowered with his chin on his chest and tried to pull his donkey jacket over his head as the close sides and roof of the roadway hurtled by. I still feel more embarrassed than he probably was.

Being born in 1948 I grew up with the Second World War writ large in my psyche. As a kid I used to play at war with all my friends and the drawings and sketching we all did were of Spitfires and Destroyers, usually in a winning battle scenario. The TV and Cinema were also full of WW2 films. It came as a surprise then that one day down the pit I was with a small group of fitters and the ‘war’ was mentioned. One of them, a middle-aged man (good grief, younger than me now), with moles all over his face (ugly I’d thought) and of a quiet and surly nature (he never spoke much), suggested that there wasn’t many left like him who had taken part in a bayonet charge in that war, “and there was no messing about like in the films, it was straight in and it was me or him”. The reaction was an embarrassed silence. We all clammed up, suddenly nothing to say when faced with a grim and ugly reality.

I did discover that several of the fitters had served in the war and many had done National Service. One told me that he was serving in West Germany and on the day before he was due to be demobbed his officer couldn’t find him anything to do so told him to dig an ‘A’ trench (in case a nuclear weapon detonated they could be snug and safe in the bottom). He refused on the grounds that he was being demobbed the following day and was damned if he was going to get filthy just for some makework. The officer just looked at him and walked away. Mutiny or what…….

Heanor College

After two years at the Arnold and Carlton College of Further Education I got good results in the G2 exams which we were told were the equivalent to GCE O level and were the College’s internal diagnostics for ONC and I was hence enrolled at the South East Derbyshire College of Further Education at Heanor. These two years were thrown down the pan. Everything went downhill, I was only interested in rock climbing and mountain walking and the motorbikes to get me there.

One of the college tutors, during general studies talked about Marxism, a subject about which we new nothing and didn’t want to know, strange considering we were in a cold war situation, and as his lesson was first after dinner break a group of us decided at the pub that if he started up again when we got back we would get up and find another place to drink in. Sure enough it happened and a group of about six of us just got up and without a bye your leave walked out and went looking for a club to go drinking in, the pubs now closed for the afternoon. It was extraordinary considering what was to happen to me a few years down the line.

Our math’s teacher at this college was another one who liked nothing better than to talk about sex at every opportunity and was often prime mover in getting one of our teenage newlyweds to elaborate on his sexual exploits which seemed to require the use not only of his bed but bed head, wardrobe, stairs, kitchen table, bath and anything they could bend their imaginations around. This lad had the strongest Nottingham accent I have ever heard and his ability to shorten even two letter words had the whole class hung up on his dialect. He seemed to try to remove all consonants from his speech and emphasize the vowels in a way that we found impossible to emulate and was probably his own specialty rather than Nottingham’s. Then one day, “And if you both cum together its call an orgasm”. We all howled with laughter and I can still see the look of puzzlement on his face as he glanced around.

Coal Face

Sometime, I think towards the end of the third year, I went to Gedling Colliery for a month to do coalface training. Gedling was fondly known as the United Nations because every nationality allegedly worked there. Pride of place, and always mentioned, were two full-blooded American Indians. Why is it that American Indians are usually referred to as ‘full blooded’? Why not ‘full blooded Pakistanis’?or ‘full blooded Italians’? Some years later I was listening in to a conversation on racist lines when one guy mentioned that he had been to China and had stood at the back of a very large pro-government demonstration and, “I could see right over their heads and it was just a mass of black blobs, everyone had the same colour hair”. These guys found something to snicker at with contempt but what he was actually pointing out was that it is not possible in this country to see such a uniformity of natural hair colour; we all display our historic tribal/clan heritage and mixture. There’s no ‘full blooded Englishman’ There’s no full-blooded American Indian either, or I miss my guess.

The purpose of this month was to acclimatize to the coalface by working as, and with, a miner. There were two of us apprentices, John Tew wasn’t from Calverton but I knew him from HTC, in fact John had caused me some embarrassment one day at the Centre. I met him as we walked in and he said, “I’ve just left my wife”. What he meant was that he had just got married at weekend and coming to work was the first time they were parted. I couldn’t find anything to say, not even ‘congratulations’ Christ we were only seventeen or eighteen and I couldn’t even afford a motorbike let alone a wife so we walked in silence.

The coal face we were assigned to was ‘handgot’ that is to say that after a machine had undercut the coal-seam and it was up to us to hack it out and shovel it onto the conveyor. The seam was a yard high and the undercut was a yard deep and a man was given a nine-yard ‘stint’ to work. At a cubic yard to the ton simple arithmetic gives nine tons to hack and shovel in a shift. John and I were each assigned a man to assist. John Tew’s man was a Jamaican called Sylvester and was the first Jamaican I ever met. The second Jamaican I was to meet was some years later and we married. Ironically, as I was meeting Sylvester, my future wife would have been arriving at Manchester Airport.

The process was to use a pick to pull the coal off the face then shovel it onto a conveyor and set roof supports, which were wooden posts. When our stint was finished we would help others who hadn’t finished and then the conveyor had to be relocated a yard forward ready for the next shift. During the coarse of that first shift three more men pushed themselves into my stint and I was too busy hacking away to take much notice. Suddenly there was a thump, felt through the ground as well as my ears; I wondered what the hell was going on. The men were a Deputy, a Shotfirer and the guy from the next stint. The Deputy and Shotfirer worked their way down each nine-yard stint, drilled holes in appropriate places in the coalface, charged them with Denispex (if my memory serves me right a sheathed explosive, meaning the explosion wouldn’t ignite any gas), crowded into the next stint and blew it. I never got over the idea that it all goes bang just a little bit too close.

The explosives made it possible to finish the stint otherwise it would have been impossible. Another surprise was the amount of Denispex that didn’t ignite. I could be picking away at the coal and suddenly find a cartridge of Denispex on the end of my pick. Looking at the coal on the conveyor always showed the telltale white powder from other stints.

There were three shifts in the system and I think they worked, one for machining the undercut, one for taking the coal and one for building the packs in the space already mined to keep the roof up. The packs were built of the stone rubble that fell out of the roof, the wooden props used, just in front at the coal face, were only adequate as a temporary measure while the coal was being taken.